by Chase Reed

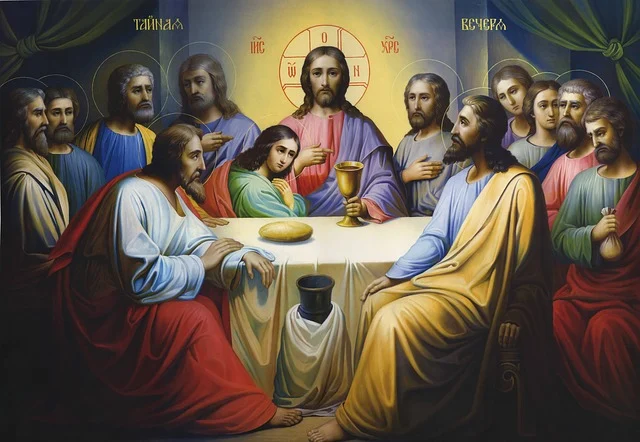

Some of the most well-known and recognizable works of art throughout history are those that depict Jesus Christ the Messiah. Da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1495–1498), Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ (1603–1604), and Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633) are a few examples of depictions of Christ that believers and non-believers alike have come to appreciate. A person is not restricted to art galleries and museums alone in order to see such images, however. Many local churches also depict Christ’s life, death, and resurrection in one form or another through media such as paintings, stained glass, statues, flags, and on printed materials. Despite the prevalence of such depictions, not all believers have been united on allowing Christ to be depicted in some form or image. The side in which a believer falls in this debate depends on their understanding of the Second Commandment and if they believe that images of the Messiah are a violation of it.

The term image itself can have a broad meaning. Therefore, this paper will distinguish between images of Christ and images of false gods. The former can be defined as the “conscious use of skill and creative imagination” towards the formation of artwork that glorifies the Messiah. The latter can be defined as “a representation or symbol of an object of worship” that a creator has “substituted for the true and living God”. Despite the creation and veneration of images of false gods being condemned universally by various denominations as an unethical practice, the ethical nature of images of Christ is contested throughout Christendom even today. The goal of this paper is to present the case that artistic depictions and images of Christ are indeed ethical as those who oppose them are in error, the Scriptures and the Tradition of the Church do not prohibit their use, and they can be applied morally as a means of explaining the life and teachings of Christ to certain demographics of local church congregants.

Understanding the Opposing Side

History and Basic Viewpoints of the Opposing Side

Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christians are virtually in complete unity in regards to supporting the use of images of Christ. The debate, then, resides between various Protestant and Evangelical denominations. Those opposed to depicting Christ include those within the Reformed denominations, the Particular Baptists, the Amish, and various independent churches. It is crucial to point out that before Christianity began, the Jewish people themselves were heavily against the use of images not sanctioned by God. Jewish historian Josephus records the time when King Herod “had erected over the great gate of the temple a large golden eagle, of great value, and had dedicated it to the temple.” This action angered many of the Jews in the area and stirred them to rebellion, as they saw such an image to be a violation of God’s Law.

The theological position these Christian groups hold to, often referred to as “aniconism,” stems partially from a synthesis of certain iconoclastic attitudes in the early church and the Jewish view of images. However, the primary root of modern aniconism is rooted in the views of the 16th century theologian John Calvin. The French reformer writes, “Should we have portraitures and images, whereby only the flesh [of Christ] may be represented? Is it not a wiping away of that which is chiefest in our Lord Jesus Christ – that is, to wit, of His Divine Majesty? Yes!” The major issue for Calvin was that, in his view, any artistic depiction of the Messiah was an insult to Christ since the artist would only be depicting Christ’s nature of humanity. This perspective was carried on primarily through the Reformed divines, as seen in their historical writings. The Westminster Larger Catechism, in Question 109, explicitly states:

- “The sins forbidden in the Second Commandment are, all…using, and anywise approving…the making of any representation of God, of all or of any of the three persons, either inwardly in our mind, or outwardly in any kind of image or likeness of any creature whatsoever; …whether invented and taken up of ourselves, or received by tradition from others, though under the title of antiquity…[or] good intent…”

It is evident from this catechetical excerpt that those groups who hold to the aniconist position are not only against images of the Father and Holy Spirit, but also of the Incarnate Christ. Likewise, such denominations like the Reformed believe that even a mental image of the Messiah is a sin forbidden by inspired Scripture. Modern Christian scholar R. Scott Clark, a proponent of this view, states, “The rejection of internal images [of Christ] is a good and necessary consequence of the rejection of external images. The god we fashion in our hearts and minds are just as idolatrous as icons of the Father, the Son incarnate, and the Spirit.” To Clark, Calvin, and other aniconists, any depiction of Jesus Christ made internally or externally is an idol made by a sinful heart.

Initial Critiques of the Opposing Side

Armed with a proper understanding of the opposing view towards artistic depictions of the Messiah, one can begin to critique the errors of those who hold to aniconism. Many questions arise from holding to a theology that Calvin, Clark, and others hold to. For example, should all artwork be considered sin since it causes us to give reverence to a human maker and distracts us from our Creator? Another question is, since Christ is “the image of the invisible God” and the disciples only beheld His flesh and not His full divinity, were they in sin according to Calvin’s view (Col. 1.15 ESV)? Taken to its logical conclusion, the aniconist position would have to answer ‘yes’ to such posed questions.

On the topic of mental images of Christ being considered sin in need of mortification, one realizes the danger of holding to such an idea when examining the issue from a scientific view. It is understood that there exists two ways of perceiving an image mentally: through imagination and imagery. Bence Nanay writes, “Mental imagery is not imagination. Imagination is (typically) a voluntary act. Mental imagery is not. Mental imagery can be, and is very often, involuntary.” With this understanding, it would then follow that anytime someone hears or reads about Jesus and involuntarily perceives Him as mental imagery, they would be in sin. And if such mental imagery is involuntary, the aniconist would have to warn believers against thinking about Christ, lest they fall into idolatry. Such an action would be contradictory, however, to the command that the apostle Paul gives to dwell on that which is true, pure, and worthy of praise, which would certainly include the Messiah within those descriptions (Phil. 4.8). The strongest arguments against the aniconist position, however, are those that deal directly with the commands in Scripture regarding man-made images and idols and the testimony of the early church on the subject of depicting the Messiah. Due to the scale of those topics, they have been relegated to the following section in order to more thoroughly analyze this ethical issue.

Scriptural and Theological Analysis

Examination of the Issue from Scripture

The Bible passage that may seem to outlaw any depictions of Christ is found within the Ten Commandments that Moses receives from the Lord. Exodus 20.4-5a states, “4 ‘You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. 5a You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the Lord your God am a jealous God…’”. In clear terms, the Lord demonstrates His distaste for idolatry and the seriousness of His people committing it. It is an error, however, to compare the act of depicting Christ in artistic ways to an act condemned by this commandment. In the Hebrew text of Exodus 4, God forbids any “תְּמוּנָ֡֔ה” or divine “form.” Professor Chad Bird expounds on this, stating, “Because God gave his people no form or likeness of himself; because they only ‘heard the sound of words, but saw no form’; they were therefore forbidden from making a form or likeness of God.” It follows why this command would be put in place when one reads of the majesty of the Incarnation in the New Testament. The Apostle Paul explains in his epistle to the Colossians that within Jesus “…the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily” (2.9). Thus, one can understand that God forbade the Israelites from depicting Him in order to properly show them who He was through the Incarnation of God the Son. The Incarnation then was God choosing a proper likeness for which His people could understand and perceive Him. Any image, then, that depicts Christ as a man is not improper as it simply reinforces the idea that God chose to take on flesh rather than to allow His Creation to choose to depict Him a certain way, as was done with the false gods. Author J. Douma expresses a similar attitude when he writes, “Artists…transgress no boundaries established by the second commandment when they convey…[what] believers in biblical times were permitted to see.” In sum, images of Christ cannot be deemed unethical in light of a proper understanding of the second commandment.

A second point from Scripture that supports the use of images of Christ is the fact that throughout the Bible, God Himself allows and sanctions certain images to be used for ethical reasons. The first example is that of the carved cherubim on the Ark of the Covenant that God has Moses create (Ex. 25.18-21). Commentator Stuart Douglas expounds on their construction, stating, “One faced the center of the atonement cover from one end, the other from the other end. Their wings were raised, so as to overshadow the atonement cover, providing a kind of symbolic partial enclosure that protected the surface.” Several chapters later, God would state in the Second Commandment that no likeness should be made of a form “בַּשָּׁמַ֣֙יִם֙ מִמַּ֡֔עַל” (“in the heaven above”). To the aniconist, it would seem God unethically asked Moses to construct two likenesses of heavenly beings for the Ark, thus causing him to sin. But understood in context as was previously explained, God was specifically forbidding in the Second Commandment unsanctioned images of Himself and the worship of any created form or false god that Man could make. A second example is the creation of the bronze serpent in Numbers 21.4-9. In this story, God disciplines the Israelites by allowing them to get sick after being bitten by snakes. When the people cry out to Him, He mercifully responds and tells Moses, “Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live” (21.8). Rather than portraying a heavenly being, Moses seems to now be breaking the other prohibition of the Second Commandment: creating a likeness of a form “בָּאָ֖֨רֶץ מִתַָּ֑֜חַת” (“in the earth below”). Yet one sees once again that God sanctions this image and uses it for the purpose of healing His people and to foreshadow the Messiah (John 3.14-15). The Israelites at the time knew (and were reminded) that it was not the bronze serpent that truly healed them, but it was God who used it for ethical means. Just as the Israelites were healed by God through the bronze serpent, believers are healed by Jesus Christ. As they perceive Him in images of His life, death and resurrection, they are reminded of the infinite and powerful mercy of God. To say that images that invoke these positive feelings towards God are unethical is to misunderstand the Second Commandment as it relates to God and requires one to ignore the passages in Scripture where God specifically tasks His people to create images.

Examination of the Issue from the Tradition of the Church

Though sacred Scripture is the only infallible authority in matters of faith and life, the Fathers of the early Church and the various ecumenical councils provide wisdom that should guide modern believers in their interpretations of God’s word. The ethical issue of depicting Christ is no exception to this. One of the earliest opinions offered on the topic comes from the 2nd-3rd century theologian, Tertullian. In his work Against Marcion, Tertullian comments on both the Bronze Serpent and Ark of the Covenant cherubim passages mentioned previously. He explains:

- “Likewise…[God] declared also the reasons, as being prohibitory of all material exhibition of a latent idolatry. For He adds: You shall not bow down to them, nor serve them. The form, however, of the brazen serpent which the Lord afterwards commanded Moses to make, afforded no pretext for idolatry, but was meant for the cure of those who were plagued with the fiery serpents…Thus, too, the golden Cherubim and Seraphim were purely an ornament in the figured fashion of the ark; adapted to ornamentation for reasons totally remote from all condition of idolatry…”

In sum, Tertullian shows that images or artwork can be made freely, especially when it is done for the ethical benefit of another and when the one who makes or sees the work has no intent of ascribing glory or worship to the work and its material itself. The aniconist simply disregards this idea: that one could create a portrait of the Messiah and be drawn to worship Christ more deeply from it. They believe that in doing so, they must be worshipping the wood or canvas or statue itself somehow. Augustine of Hippo, one of the theologians most beloved by aniconists such as the Reformed Churches, provides further commentary on the issue. In his work, Contra Faustum, Augustine defines what worship truly is, writing:

- “What is properly divine worship, which the Greeks call latria, and for which there is no word in Latin, both in doctrine and in practice, we give only to God. To this worship belongs the offering of sacrifices; as we see in the word idolatry, which means the giving of this worship to idols. Accordingly we never offer, or require any one to offer, sacrifice to a martyr, or to a holy soul, or to any angel. Any one falling into this error is instructed by doctrine, either in the way of correction or of caution. For holy beings themselves, whether saints or angels, refuse to accept what they know to be due to God alone.”

In clear words, Augustine equates proper worship to that of sacrifice in this text. Further, he adds that the Christian church has never approved of any sort of sacrifice to something that isn’t God Himself. To equate the creation or enjoyment of a depiction of the Messiah with worship is to have a false and weak understanding of what worship really is. It would certainly be true that if a person were making sacrifices to a portrait or statue of Christ they would be doing something unbiblical and unethical. Yet this sort of behavior is not occurring in churches that depict the Savior nor is it the prerogative of those who create artwork of Christ. This idea is echoed by John of Damascus, a well-known defender of icons from the 7th-8th century. He states:

- “Of old, God the incorporeal and formless was never depicted, but now that God has been seen in the flesh and has associated with human kind, I depict what I have seen of God. I do not venerate matter, I venerate the Fashioner of matter, who became matter for my sake and accepted to dwell in matter and through matter worked my salvation…”

John reiterates two very important points. First, God the Son has taken on flesh, choosing Himself how He should be depicted. Second, the one who depicts God the Son does not intend to worship the matter used to create the depiction, but instead understands that it aids in the worship given to the one who Creates all things, Jesus Christ Himself. As it has been demonstrated, images of Christ are ethical tools not prohibited by Scripture in the eyes of the Church Fathers.

It was ultimately at the seventh ecumenical council, also known as Second Council of Nicaea or Nicaea II, where the ethics of portraying the life of the Messiah was truly contested and settled. Although the use of depictions of Christ had been defended by various church fathers, strong iconoclastic controversies rocked the church in the 8th and 9th centuries. After emperor Leo IV passed away, his widow Irene acted as regent for their son Constantine VI and overturned certain iconoclastic policies within the empire. Under her instigation, the Second Council of Nicaea convened in 787 and condemned the aniconist view, while also affirming the ideas put forth by John of Damascus. The officially published documents of the council, as recorded by the bishops and clergy in attendance, lay out the position as follows:

- “We, therefore…define with all certitude and accuracy that just as the figure of the precious and life-giving Cross, so also the venerable and holy images, as well in painting and mosaic as of other fit materials, should be set forth in the holy churches of God…the figure of our Lord God and Saviour Jesus Christ…For by so much more frequently as they are seen in artistic representation, by so much more readily are men lifted up to the memory of their prototypes, and to a longing after them; and to these should be given due salutation and honourable reverence, not indeed that true worship of faith which pertains alone to the divine nature…For the honour which is paid to the image passes on to that which the image represents, and he who reveres the image reveres in it the subject represented.”

Though the language may seem strange to the 21st century Christian, what the council is saying is neither complicated nor contradictory to God’s word. In essence, images of Christ are ethical because they draw the believer to not worship the matter of the image, but to worship He who is represented: Christ Jesus. In other words, to have a portrait of Christ in one’s home is no more idolatrous than having a portrait of a loved one hanging in one’s living room. With this understanding, it is clear to see why the position laid out by Nicaea II is crucial to understanding the ethical nature of images of Christ from a historical perspective.

The Ethical Applications of Depictions of Christ

As it has been established that depicting Jesus Christ in the form of an image or icon is not unethical in terms of the second commandment, the question to address now is, “What is the ethical use in portraying the Messiah at all?” The answer to this question crosses all eras of Christian history and continues into the modern day. The ultimate purpose of portraying Christ is to proclaim the Gospel in a different format, especially to those who may not be able to verbally receive the Good News of Christ. E. M. Catich explains that the “function of religious art in all ages is to help people in their devotional needs; to help them approach more easily and understand more clearly divine truths; and ultimately to move them, by the aid of grace, to closer union with God.” If this principle is true, how much more does Christian art that accurately depicts the Messiah assist those who may be unable to read the Bible for themselves or hear a sermon? It is for these types of individuals that the ethical nature of images of Christ is most clearly applied. Images of Christ are not intended to function as some sort of pagan idol like some aniconists would believe. Rather, images of Christ are meant to be a tool for assisting those who are illiterate or deaf, as well as an instruction tool for young children, in order that they may learn to draw near to the Savior just as a typical adult Christian would when they read the Scriptures or hear an expository sermon.

This idea is not a new one. Images of Christ, as well as those of Old Testament and New Testament saints, have allowed certain individuals to learn about Christ throughout the many centuries of the Church. For example, during processions and liturgies on Good Friday in the early church, Christ would often historically be depicted as a Man of Sorrows hanging on the cross. To one who cannot read the Bible or understand sermons, they would look upon such an image and understand that this death was no ordinary crucifixion. Looking at the data of illiteracy rates that existed in the days of the early church furthers the need for such pieces of art. In the days of the apostles, it is believed that the literacy rate in the Greco-Roman world was only 5 to 15%. Daily Bible reading would certainly be an impossible task for a majority of new believers. Art of the Messiah, then, became a way for the illiterate to learn about who Christ was. Likewise, anyone who was born deaf or became deaf through a tragic accident in the early church would have seen images of Christ as a means of learning about the Gospel. Surely, portraying Christ for these often neglected individuals is in line with biblical teaching. The Gospels record Christ saying that as one does good “to the least of these” so too do they do good to Christ Himself (Matt. 25:37-40). Studies and statistics indicate that there is a large population of believers in the modern day who are struggling with both illiteracy and deafness. These groups are already lacking discipleship, so it follows that the church should learn from its past and adapt its models of discipleship using methods such as art in order to reach these individuals. It is therefore illogical to posit that proclaiming the Gospel to the illiterate or the deaf in such a way is unethical or unbiblical.

One counter-argument the aniconist may respond with is, “Allowing images of Christ may lead to people abusing His image in art.” It certainly is true that some will seek to portray Christ doing something sinful in order to spite the Church or others will portray Him in a way to further a political or social agenda. The simplest refutation to this is simply this principle: virtually all good things can be abused. Just as a hammer is used to build homes, the criminal finds a way to use them to bash in the head of their enemies. Should hammers then be made illegal? In the same way, the potential abuses of images of Christ do not outweigh the benefits of what occurs when He is portrayed appropriately. When Mel Gibson’s filmThe Passion of the Christ (considered by many to be a generally faithful and appropriate depiction of Christ) released in theaters, a Barna study found that roughly 16% of viewers were positively challenged in how they viewed the Christian life and the Messiah Himself. Others reported attending church or beginning to pray more often upon viewing the film. When Christians portray Christ according to the Scriptures in the form of images or even films, it is evident that God is powerful enough to work in the lives of those who experience such works of Christian art.

Conclusion

Although not a primary issue like that of the Trinity or salvation, the issue of creating and using images of Christ is a crucial ethical issue as it pertains to reaching those who may not be able to receive the Gospel as the typical believer can. When examined from the words of Scripture and the Tradition of the Church universal, it is evident that images of Christ are in no way idolatrous in the way a carving or painting of a pagan god is. This is not to say that churches who hold to the aniconist position are mistreating or neglecting those who are illiterate or deaf. However, such denominations are indeed missing out on a historic, biblical, and ethical method of discipleship that not only reaches neglected demographics, but one that ultimately draws an individual into greater love for the Messiah. This paper agrees with the aniconists that any image of Christ that depicts Him wrongfully, such as Him committing sin or doing something not found in Scripture, should be immediately disregarded. But if a church or an individual Christian creates an art piece, such as a painting or sculpture, that portrays the blessed Savior as the Gospel authors wrote about Him, then such art can be enjoyed by believers and shared with unbelievers in the hopes that they would want to seek the Savior and come face to face with Him joyfully in the next life.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Ashley, Timothy R. The Book of Numbers. Edited by R. K. Harrison and Robert L. Hubbard, Jr. NICOT 4. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Co, 1993.

- Bird, Chad. “Are Images of Jesus a Violation of the Commandments?” 1517: Christ For You, 20 Feb. 2021, https://www.1517.org/articles/are-images-of-jesus-a-violation-of-the- commandments.

- Calvin, John. Sermons on Deuteronomy. Carlisle, PA: Banner of Truth, 1987.

- Catich, E. M. “The Image of Christ in Art.” The Furrow 8, no. 6 (1957): 373–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27657193.

- Clark, R. Scott. “Are Mental Images Of God Unavoidable?” The Heidelblog: Recovering the Reformed Confession, 8 Sept. 2021, https://heidelblog.net/2021/09/are-mental-images-of-god-unavoidable/.

- Douglas, J. D., ed. The New International Dictionary of the Christian Church. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1974.

- Douma, J. The Ten Commandments: Manual for the Christian Life. Translated by Nelson D. Kloosterman. Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1996.

- Dowley, Tim. Introduction to the History of Christianity. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1990.

- Drewer, Lois. “Recent Approaches to Early Christian and Byzantine Iconography.” Studies in Iconography 17 (1996): 1–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23923639.

- Holmes, Peter, trans. “Tertullian’s Against Marcion, Book II.” Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 3. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1885. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight, https://www. newadvent.org/fathers/03122.htm.

- St. John of Damascus. Three Treatises on the Divine Images. Translated by Fr. Andrew Louth. Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003.

- Josephus, Flavius. “Concerning The Disease that Herod Fell Into and the Sedition Which The Jews Raised Thereupon; With The Punishment of the Seditious.” Chapter VI of Book XVII, in The Complete Works. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. https://ccel.org/ ccel/josephus/complete/complete.ii.xviii.vi.html.

- Kinney, Brian W., ed. The Confessions of Our Faith: The Westminster Confession of Faith, The Larger Catechism, and the Shorter Catechism. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Publishers, 2007.

- “Literacy Statistics 2024-2025 (Where we are now).” National Literacy Institute, 2024, https://www.thenationalliteracyinstitute.com/post/literacy-statistics-2024-2025-where-we-are-now.

- Merwe, Christo van der, The Lexham Hebrew-English Interlinear Bible. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2004.

- Nanay, Bence. “Mental Imagery.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2021. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/mental-imagery/#ContMentImag.

- “New Survey Examines the Impact of Gibson’s ‘Passion’ Movie.” Barna, 10 July 2004, https://www.barna.com/research/new-survey-examines-the-impact-of-gibsons-passion-movie/.

- Paley, Justin P. “Pauline Pseudepigrapha and Early Christian Literacy: Are the Clues Hidden Right in Front of Us?” Religions 14 (2023): 1-13.

- Percival, Henry, trans. “Second Council of Nicæa.” Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, vol. 14, Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1900. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight, http://www.newadvent. org/fathers/3819.htm.

- Stothert, Richard, trans. “Augustine’s Contra Faustum, Book XX.” Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, vol. 4. Edited by Philip Schaff. Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1887. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight, https://www.newadvent.org /fathers/140620.htm.

- Stuart, Douglas K. Exodus. Edited by E. Ray Clendenen, NAC 2. Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2006.

- Williamson, Dana. “‘Not a moment to spare’ in reaching Deaf, Chitwood says.” International Missions Board. 21 April, 2022. https://www.imb.org/2022/04/21/not-moment-spare -reaching-deaf-chitwood-says/.

- Youngblood, Ronald F., et al. Nelson’s New Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1995.

Leave a comment